The Fundamental Architecture of Our Lessons: A Critical Examination of Lesson Design

A critical exploration of how lesson structures evolve from insightful practices to rigid templates. This blog challenges standardisation, urging a shift from compliance to teacher autonomy and expertise.

Mark Martin

10/18/20255 min read

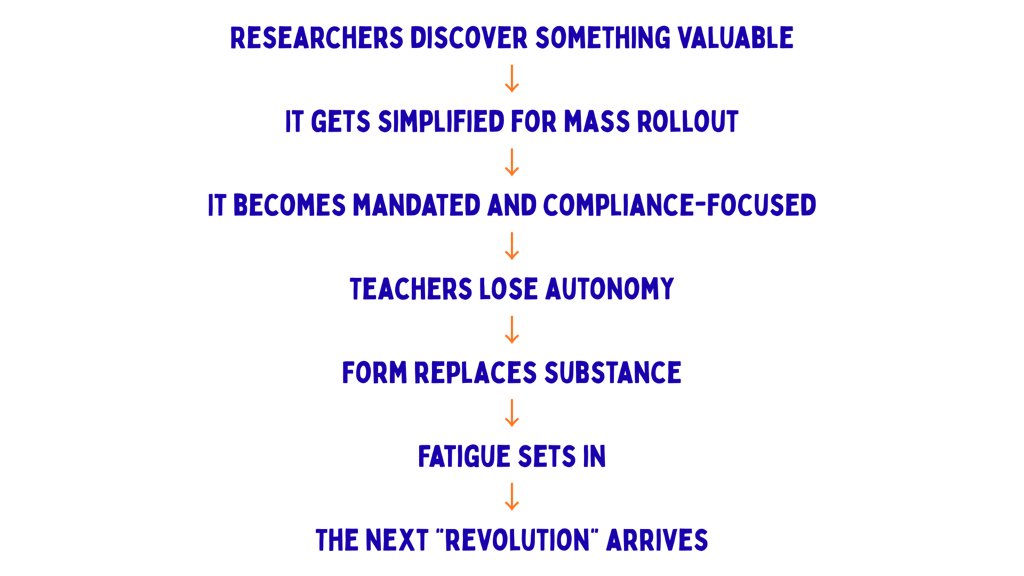

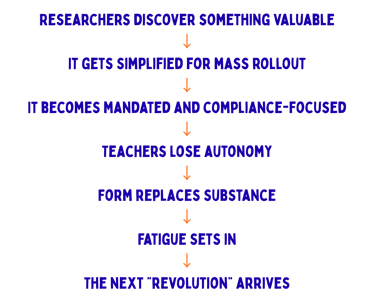

Lets zoom out and look at the pattern over time:

1900s: Herbartian five-step lessons were the answer

1970s: Objectives-based teaching (Bloom, Mager) was the answer

1990s: Constructivist discovery learning was the answer

2000s: Three-part lessons were the answer

2010s: Student-centred differentiation was the answer

2020s: Cognitive science is the answer

Each one was supposed to revolutionise teaching. Each one was based on genuine insights. And each one became bureaucratised, mandated, template-driven, and eventually divorced from actual thinking about learning.

This cycle explains why, despite knowing more about learning than ever before, so many lessons feel rigid, formulaic, and reduced to tick-box exercises. It's why teachers with decades of experience roll their eyes at each new initiative on INSET day. And it's why I keep returning to a simple yet subversive question:

Who is our teaching routine actually serving? students, school leaders or policy

Look at any educational "breakthrough," and you'll find genuine insights at its origin. Johann Friedrich Herbart's five-step lesson plan from the 19th century emerged from real observations about how students learn:

Preparation – connecting new material to students’ prior knowledge

Presentation – introducing new content clearly

Association – linking new knowledge to what students already know

Generalisation – drawing broader principles or rules

Application – practising and applying the new knowledge in different contexts

The constructivist movement brought valuable insights about active learning. Even the much-maligned "starter-main-plenary" structure contained wisdom about cognitive warm-up, focused work, and consolidation. But each of these insights calcified into dogma, their original purpose buried under compliance paperwork. Before industrialised schooling, teaching looked very different

Socratic dialogue – questioning based on student thinking

Apprenticeships – learning by doing alongside skilled mentors

Tutorial systems – individualised guidance

Religious instruction – reflection and critical thought

The rise of standardised, industrialised schooling prioritised efficiency, accountability, and scalability, replacing dialogue and individualisation with rigid templates. The three-part lesson structure prevailed because:

Accountability culture – administrators wanted observable, measurable teaching

Teacher training – easier to train new teachers with formulas

Ofsted/inspection regimes (UK) – needed "evidence" of good teaching

Curriculum coverage pressure – belief that structure ensures everything gets taught

Risk aversion – structured lessons feel "safer" than free-flowing dialogue

These weren’t formalised "discoveries," but organic practices that simply worked because they put learning, not systems, first.

The rigid lesson plan structures we know today are surprisingly recent. The “starter-main-plenary” model, now ubiquitous in the UK, emerged only in the late 1990s with the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies. Today, templates and even mandatory requirements exist depending on your MAT, school, or institution:

Lesson Objectives (5 minutes) – Introduce the lesson aims and success criteria.

Starter Activity (5 minutes) – Hook students’ attention and activate prior knowledge.

Main Activity (40 minutes) – Deliver new content, guide practice, and support learning.

Plenary (10 minutes) – Review key ideas, assess understanding, and encourage reflection.

As you go through the motions of a lesson, you internally ask yourself:

When should I change activity?

How do I evoke curiosity right now, in this moment?

When does the lesson need a pause for silence and reflection?

Should I test learning now or wait?

Is this the moment to check on that individual, did they eat breakfast, how are they feeling? Where are the gaps in learning revealing themselves?

How do I refocus a drifting student? When must I deal with behaviour that threatens the lesson’s outcomes?

These building blocks of responsive teaching cannot be scripted or templated.

In my book, I propose My Teaching Routine, a seven-stage framework emphasising flow and flexibility:

Connect – genuinely engage students at the start

Demonstrate – model new learning clearly

Activate – prompt students into action with minimal teacher talk

Facilitate – guide learning responsively

Collaborate – foster peer elaboration

Consolidate – synthesise understanding meaningfully

Reflect – encourage metacognition

This routine centres on the holistic learner, a complex individual shaped by emotions, experiences, and perspective. The focus shifts from teacher performance to student thinking, from compliance to genuine engagement.

The meaning of education is not to pour knowledge in, but to draw out understanding and connect it to the wider world. This requires the teacher to have knowledge, patience, and empathy. Over the last few years, the structure of the lesson has been shifting to focus on:

Retrieval and activation of prior knowledge

New learning with managed cognitive load

Elaboration and connection-making

Deliberate practice towards automaticity

Spaced review over time

This emerging paradigm could change everything about how we plan.

Instead of asking, “What activities will fill this hour?”,

we ask, “What cognitive processes need to happen for learning to stick?”

Instead of, “What’s my starter activity?”,

we ask, “How will I activate prior knowledge and create retrieval strength?”

Instead of, “What’s my main activity?”,

we ask, “How will I manage cognitive load? What’s the worked example? Where’s the deliberate practice?”

Even "brain gym" lessons, while promising, risk becoming the next rigid template. The cycle persists because we mistake the format for the principle. We see successful Socratic dialogue and mandate questioning techniques. We observe effective direct instruction and script teacher talk. We recognise the value of retrieval and require daily quizzes.

Every time, we take something context-dependent and make it universal. We take something flexible and make it rigid. We take something that requires expertise and make it a checklist. In the worst cases, we dehumanise the learning experience. Breaking the cycle requires fundamental shifts:

From templates to principles – understand why a lesson activity works so teachers can design it flexibly

From compliance to capability – build teacher expertise rather than enforcing uniformity

From standardisation to context – recognise that different situations require different approaches

From observation to trust – give teachers professional autonomy to make real-time decisions

The future isn’t about finding the perfect components, activities, or experiences that make a good lesson. It’s about understanding how these elements interact dynamically:

How a moment of curiosity can transform into deep inquiry

How a well-timed pause can consolidate learning better than any worksheet

How checking whether a student ate breakfast might be the most important pedagogical decision of the day

These aren’t items on a checklist, they’re professional judgements that require expertise, sensitivity, and freedom. In another decade, we’ll likely be here again, excited about the next revolution promising to fix everything unless we recognise the cycle. Unless we stop looking for perfect templates and start trusting teachers to think, adapt, and respond to the complex humans in front of them.

After teaching at every level—from primary school to university—and writing a book on teaching and learning, I've identified a troubling pattern in education.

We rarely question the fundamental architecture of our lessons:

Why we teach the way we teach, why certain classroom rituals persist, who actually benefits from them, and whether we can prove they work across diverse educational settings

What fascinates me is the construction of lessons themselves: these living, breathing experiences we create with students. Each lesson is an architectural feat, built from assumptions we seldom examine yet shape millions of learning moments every day.

Watch any educational innovation long enough, and you'll witness the same patten: